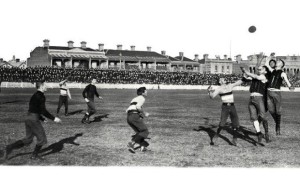

Each stadium has its own architecture. The gently rising terraces of suburban football grounds or the steep stands of the MCG. Stadium architecture is a response to the size of the field upon which the game is played. Australian football developed in borderless paddocks: and the grounds we have now reflect the early expanses. I wonder: when did the grounds become oval, when was the scoring system developed, entrenched? Behind posts, apparently, were added to the goals in 1866. During the earliest games a round ball was used. A 100 minute time limit was enforced from 1869.The game was initially played by cricketers to stay fit in the off-season: and how quaint this now seems, given the extraordinary athleticism of so many footballers in comparison to relative slowness of cricketers (although that too is changing). And so footy made it onto the turf of the MCG in 1876 and that perhaps entrenched the ovalness of footy fields. But, I wonder if other shapes of fields remained in use. Although footy is ‘Australia’s game’ many of the cricket fraternity regard footy as a little too rough and its fans a little too uncouth. And this too is a generalised cliché: the sport doesn’t define the behaviour of player, supporters.

Footy ovals – even in the streamlined AFL – remain of varying shapes and sizes. Teams become more comfortable playing on their home ground. The Tiges look best when playing on the MCG and always look as if they’re playing away at the Dome even when it is a home game. The SCG is short and narrow. Geelong’s ground is long. Subiaco has ‘broad expanses’: and one can be reminded of the emptiness of the Australian landscape. The intense tackling of Sydney’s teams in the mid-2000s and Ross Lyon’s St.Kilda teams were honed at the smaller venues. The Tiges are proud of their ground which now has the dimensions of the Dome – at least they can become more familiar with their other home ground. The poor quality of the training ground was considered as one of the reasons for the long years of underperformance (not that they are necessarily over). Geelong famously plays through the corridor, probably in part because their home ground has shallow pockets.

The crowd of a footy game is easily distinguished from the crowd that watches a theatre performance. Indeed, those who a performance of the arts are classified as an audience. A crowd watches aggressively: interjecting, shouting, abusing, supporting. An audience watches (consumes) silently and in considered appreciation. This distinction is not necessarily stable or inherently true: there was a time when audiences too would interject, abuse or break out into cheering. Upon the premiere of Gustav Mahler’s fourth symphony, the audience (crowd?) demanded that it be played again – immediately. During performances of Wagner operas, the crowd (audience?) would demand that particular sections be sung again (immediately) such was their beauty. In an age when instant replays and DVDs of highlights weren’t available, there were other ways of re-experiencing what one imagined to be beautiful. And, of course, there is the famous incident of fights breaking out after the premier of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. The so-called fine arts can also arouse hostile reactions. These were times, arguably, before such music became classified. Audiences didn’t go to performances of Mahler’s symphonies looking for a safe and comfortable night’s entertainment: they went looking for something new. And sometimes this new was shocking – and the audiences were unsure of whether or not they enjoyed it.

The footy crowd/audience differs not only from that of a theatre going audience/crowd but also that of other sporting crowds. The tennis crowd is admonished by the umpire who sits high upon a chair. The players can complain to the umpire regarding the crowd. Officials at golf tournaments hold up signs bestowing silence upon those watching. The players are expected and regard it as obligatory that they perform their sports in the mythical silence of a library. Silence is dignified: allowing for concentration. I think of religious sermons and the audience of the faithful watching on – few probably listening attentively – in earnest, showing off their piety. Many take the moment of silence as an opportunity to sleep; just as many do in a cinema. But, perhaps this act of falling asleep in the dark of a cinema is less voluntary; and perhaps an accidental and passive act of film criticism. The darkness of the cinema alerts one’s senses to sound; the acoustics of churches magnifies the slightest of sounds. To be noisy is to interfere with the concentration and pleasure of others, or to be irreverent and insulting of the preacher.

The silence expected at tennis matches and golf tournaments is also a result of the proximity of the audience to the players themselves. These are considered games that require a high degree of finely tuned concentration: logic, reason, scientific judgement. But the crowd of a boxing match (not ‘game’) is also close: so close that those in the first row may be struck with the boxer’s sweat. Boxing also requires an intensity of concentration and judgement surely equal to that of tennis or golf. Players of sport will talk about being ‘in the zone’ and not hearing the crowd. At other times they will speak of how the crowd’s noise, and the support of their team in particular, was instrumental in raising their performance. At boxing matches, crowds will cheer on the final frenetic moments of the last round: willing the boxers on to give their all. While fools in the audience (crowd?) of a tennis match will interject seeking to distract a player at the moment before he or she hits a shot. It is up to the players themselves to choose when they do or do not hear the crowd. In these cases, listening/hearing is not something passive and automatic. The incident in which Adam Goodes pointed to a member of the crowd for racially abusing him was a case in point: Goodes was hardly listening to everything the crowd was shouting. But, he heard the racist statements and couldn’t un-hear them and thus he acted in the manner he did.

The broad expanses of footy stadiums gives rise to a soundscape of diffused support and abuse. There is little collective singing, chanting. The slow ‘Col-ling-wood’ ‘Col-ling-wood’ or ‘Free-yo’- ‘Free-yo’ chants are rare exceptions and are only possible, or heard, at moments of great or impending victories. Most common are the individual shouts of the crowd whose voice probably reaches no further than a few rows in front of him or herself. Synchronised chanting, supporting takes the form of ‘Team name’ followed by clap-clap-clap. But this is tedious and hackneyed. Again, it only emerges during a team’s run-on, or emerging victory. The gestures of so-called cheer squads are exaggerated partly in order to make up for the easy manner in which their shouting dissolves into the empty space of the stadium. The fan who was pointed out by Goodes was shocked not only for having being put into sudden public attention but for the realisation that Goodes had heard what she had said. Her racist statement had been heard by the target; it hadn’t dissolved into the noise of a stadium.