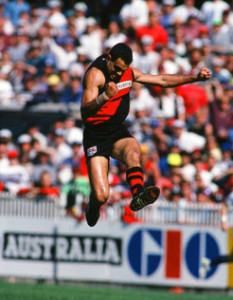

Midway through the first quarter of the 1993 grand final between Essendon and Carlton, Michael Long received a handball from Sean Denham and then ran on the southern side of the centre square of the MCG. His light frame moved across the ground, as if his feet were barely touching the ground. His face showed his effort, his focus, his concentration. He was still far from the goals – perhaps 70 meters – but, I imagine, he was already visualising the ball going through them. He bounced and he weaved. And then, having kicked the ball along a low trajectory, Stephen Silvagni made a beautiful lunging dive and touched the ball, perhaps before or perhaps after it crossed the line. The goal umpire, caught up in the beauty of Long’s run, had no hesitation in calling it a goal. Silvagni, resplendent in his long sleeves on the beautiful spring day, hunched over in despair at the futility of his efforts. Probably he was unhappy at the role he had to play in this drama. But without the opposition, Long couldn’t have created his masterpiece. Silvagni, unlike so many players, didn’t remonstrate with the umpire, didn’t whinge or complain, he accepted that the umpire had considered it to be a goal.

Long’s goal was one of the great moments for the Essendon Football Club that day. It was an anticlimactic game for Carlton fans who saw their team wilt under the pressure and exuberance of the young Essendon team. At the end of the day’s play, Long was interviewed and asked about his running goal – the goal that audaciously stated it would be Essendon’s day. Long, later in the game, had also laid on the ground for a few moments – seemingly taking a rest. His pose seemed more that of the beach than of the footy field. Lying outstretched he rested on his elbows. The interviewer – who had called him a ‘boy’ at the moment of his goal (‘look at this boy go’) – asked him what he was doing. Long replied, ‘looking for witchety grubs’. And thus, in his nonplussed and ironic manner, Long had simultaneously appropriated and countered the stereotyping of aboriginal footballers. So common is it for aboriginal footballers to be described as showing their ‘magic’: as if it is a natural, inherent ability, requiring no training. But, methinks it also relates to the phrase ‘black magic’ (re: heathen, unchristian, uncivilised) . So common is it for players of aboriginal background to be grouped together – i.e. the three amigos of Carlton – Eddie Betts (now at Adelaide), Chris Yarren and Jeff Gartlett. Paul Roos, venerable coach of Melbourne, premiership coach of Sydney, doubted the tank of aboriginal footballers. This is the man throughout much of his career has coached Adam Goodes and Michael O’Loughlin: both players of 300 games.

***

Jimmy Nelson is having an exhibition at the Volkenkunde Museum in Leiden. The museum modestly states that it is the oldest ethnographic museum in the world, having been founded in 1837. Such a museum doesn’t come into being without the aid of a broad colonial network: and indeed, the collection of artefacts from Indonesia are dense and rich. Elsewhere in Leiden, is the collection of the KITLV library with some hundreds of thousands of artefacts, books, documents, manuscripts. There is also the Siebold House with its collection of Japanese maps, objects, paintings. But it is not cool to be colonial or neo-colonial and these museums are, in one way or another, attempting some kinds of re-consideration of their role in this little town with its big university and research community. Leiden changes reluctantly. It sits apart from the hedonism of Amsterdam, the administration of The Hague and the stylish modernism of Rotterdam and its Rotterdammers.

Indonesiana is common throughout Leiden. On the shelves of people’s homes that front on to the footpaths, one sees the typical tourist artefacts brought from Yogyakarta or Bali: small metal models of Dutch bicycles – sepeda onthel in Indonesian – figurines of Javanese or Balinese dancers. Many use batik cloth to cover the dinner tables. Some of the more fashionable have more contemporary products from Indonesia: fashionably designed batik, or panniers on their bicycles made from Indonesian soap packaging. There are numerous apparently-Indonesian restaurants in Leiden, evoking ‘Indonesia’ or, rather, the Dutch East Indies, in one way or another. If ‘Indonesia’ becomes a part of a general conversation, it is often referred to as being visited as part of a semi-historical holiday. People visit the cities and seek out the homes of where their parents or grandparents lived. One friend tells me, ‘my father was one of the stupid guys who tried to maintain Dutch power in Indonesia at the end of the 1940s’. Often one hears the casual laments about the ‘stupidity’ or failure of the Indonesian nation. Some speak nostalgically saying how much they would have liked to have been a part of the colonial enterprise, imagining how well they would have done. Yes, with no sense of irony or self-critique.

There are three main sections to the Indonesia room at the Volkenkunde. This collection holds something of a pride-of-place: for, visitors must pass through it before arriving at the often rather elaborate and intensely curated temporary exhibitions. The main part of the collection consists of the typical anthropological artefacts: statues, clothes, models, jewellery, weapons, maps and explanations. There are massive Hindu sculptures stolen from East Java. Along the main wall is a huge projection of recent footage collected by the KITLV as part of their Recording the Future project. These are scenes of everyday life and contrast with the formality, fragility and singularity of the objects that are presented behind the glass cases. The footage shows people cooking, people on their way to the mosque, people at play. Behind this wall, and in the room’s smallest section, is a space used for temporary photographic exhibitions. On this occasion, there is a series of photographs by Annemarie Ruys. Her photographs are of young and rich career-women: they are shown in the context of their homes, at their friends houses or with their boyfriends or, with their fully-groomed pet dogs.

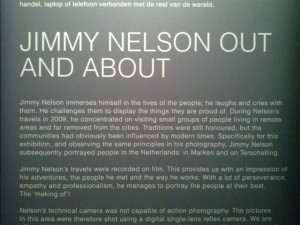

Jimmy Nelson (b.1967) is an English photographer based in The Netherlands. His exhibition is titled ‘Hail the People’ and is curated in collaboration with his own production team based around his Before They company. ‘Before They’ is a shortening of ‘Before They Pass Away’, which is the title that appears on the website, on the Facebook page and throughout the exhibition. The purpose of the exhibition, and Nelson’s photographic career, is to capture images of peoples whose traditions are under threat – from ‘change’, from ‘modernity’, from ‘the outside world’, from ‘others’. So, most commonly, Nelson’s photography takes place in far-away settings – those places that are difficult to reach by plane, boat, train. Places that have little infrastructure. Nelson too is part of the exhibition: he himself is photographed photographing his subjects. We see him and his photographed subjects in wild ranges of mountains, great expanses of ice and snow.

Nelson’s photographs continue the practice of colonial photography in an uncritical manner. He is educated, articulate and smartly dressed and fluent in English and Dutch at least. He is privileged to be able to travel where he wants to for the purpose of his career and work. My discomfort with the exhibition is based on the degree to which he has sought to make himself central to the exhibition. The exhibition’s discourse is framed around his heroic acts of capturing something ‘pure’ before it becomes besmirched by change, modernisation (money) and the ‘outside world’. What is missing from Nelson’s awareness and his exhibition, is any attempt to articulate how these people are already engaging with the forces of modernity with the otherliness of others. Nelson, simplifies these people and their context, reducing them to exotic caricatures. Too slick, too articulate by half.

***

Before the playing of the first so-called ‘Dreamtime at the G’ game some ten years ago, a columnist stated that Richmond had no player of aboriginal descent in the team. Perhaps Shane Edwards wasn’t black enough. Perhaps Shane Edwards hadn’t been spectacular enough as a player. Perhaps Shane Edwards was too workmanlike and regular. Edwards is a consistent and good player. His qualities as a player probably didn’t remind the commentators – those masters of formulaic phrases – enough of the stereotype of an ‘aboriginal’ footballer and thus Edwards was shorn of his identity. No one cared to inquire; the story had been written. And after the journalist(s) had realised their mistake, Edwards has now become a poster boy for the Dreamtime at the G game. The Herald Sun showed a portrait of Edwards dressed up in his Richmond uniform and covered in a cloak of animal skin. He’s handsome and stares down the lowly positioned camera. In an interview a couple of years ago regarding the game, he stated that many players coming from aboriginal communities find it difficult to settle into Melbourne. ‘I found it difficult enough and I came from Adelaide’. Probably that’s not what the journalists wanted to hear. His was a transition from one urban centre to another and thus didn’t match with the idea of the poor, ill-equipped, lonely aboriginal footballer who comes from the middle of nowhere to make it big in the city.

Shane “Titch” Edwards, aka Shedda

Shane “Titch” Edwards, aka Shedda

The AFL likes to regard itself as being at the forefront of reconciliation and other supposedly progressive social issues. Players such as Long and Goodes have made bold stands against the everyday racism within the AFL. The AFL forgets that it forbade Long to speak at the supposedly reconciliatory press conference between himself and Damien Monkhorst. Probably, the AFL needs to beat its chest so loud and strong about its ‘progressive stance’ towards combating racism because it has harboured so much racism in the past: ‘what happens on the field, stays on the field’, ‘harden up’, ‘look at that boy go’, ‘the three amigos’ etcetera. I like the demeanour and manner of Shane Edwards – he’s quietly spoken, gentle and plays by the rules. But next time someone asks him to put on some animal fur coat for the sake of a footy game, he should tell them to get stuffed.